When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 25, the trade-off for the West between diplomacy and force was immediately complicated. Military engagement plays to Russia’s strengths. Sanctions, on the other hand, play to the strengths of the US and its allies.

Anatomy of a Sanctioned Economy

A full sanctions policy usually involves a mixture of: halting trade, blocking private banks from correspondent banking and/or financial communications, and preventing the public sector from managing the resulting crisis. FT is maintaining a comprehensive list of the sanctions here. But what is the overall effect on Russia’s economy?

PUBLIC FINANCE

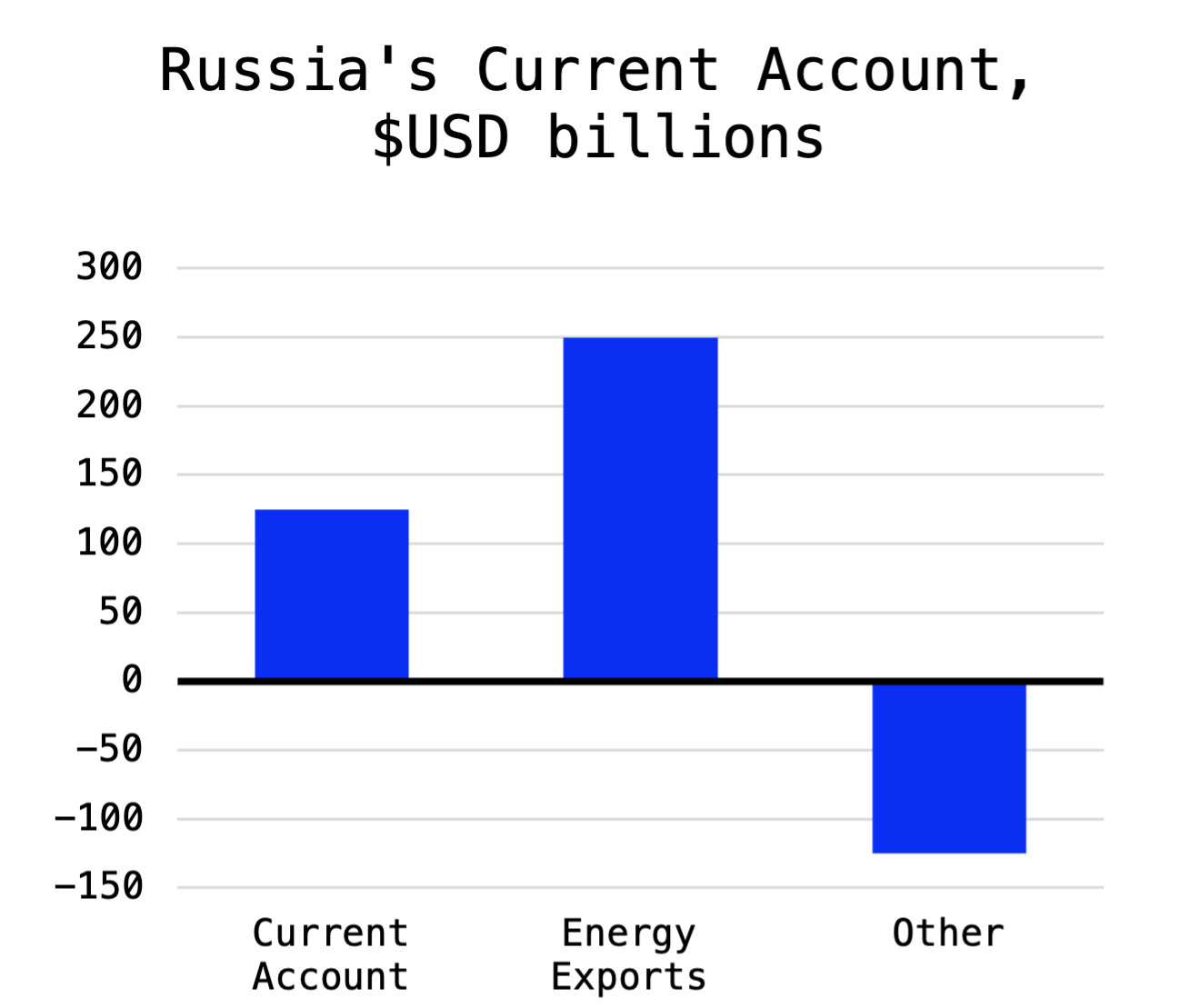

Sanctions usually raise borrowing costs, so the issuing of sovereign debt has been suspended. Because new debt is normally issued to reimburse bonds coming due, sanctions also limit Russia’s ability to refinance debt. Major emerging market economies rely on financial markets to finance their budget deficits. Since the 1998 crisis, Russia has been fiscally disciplined, and its public debt—which was downgraded to junk by S&P last week—is quite low at 16%. It has a sizable balance sheet to finance it. It maintains twin-surpluses; Russia’s first-order relief from its liabilities is its current account surplus, $120 billion in 2021. And unless the allies sanction energy output (50-60% of Russia’s total annual output), rising energy prices mean positive annual revenue forecasts for Russian firms.

Then there’s the ruble: hyperinflation is to be avoided at all costs. Nearly 75% of Russia’s consumer goods are imported. A rapidly devaluing ruble means the cost of these imports, which are denominated in foreign currencies, will surge in price. Those who borrowed in foreign currencies will be unable to repay debt that is worth more in local currency than they can afford.

PRIVATE BANKING

According to IIF, Russia’s banking system assets are around 100% of its GDP (compare to Brazil, at around 160%). To damage it, the prime targets were state-controlled Sberbank (38% of Russia’s banking system) and VTB (20%). Sanctioning private banks means customers can no longer use US-affiliated payments (e.g. Visa, MasterCard-issued credit cards) or payments platforms (those cards loaded onto Apple Pay, Google Pay). Sberbank holds half of Russia’s domestic savings deposits. It’s the largest bank to be shut out of the US correspondent banking system.

The allies dialed this up by also banning these banks from SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, a common-language financial messaging system. SWIFT is not a payments or settlement system, but it makes payments and settlements simpler, faster, and cheaper. When the largest banks are excluded from financial communications, it brings into question their ability to process transactions and therefore their overall solvency, which precipitates bank runs.

INTERNATIONAL FINANCE

Because major Russian banks are unable to maintain correspondent banking relationships, they cannot transact in dollars. A sanctioned Russian bank attempting to settle a transaction with a foreign bank will be rebuffed. This transaction would have been sent via SWIFT, but it’s the correspondent banking relationships that are the necessary factors in international finance.

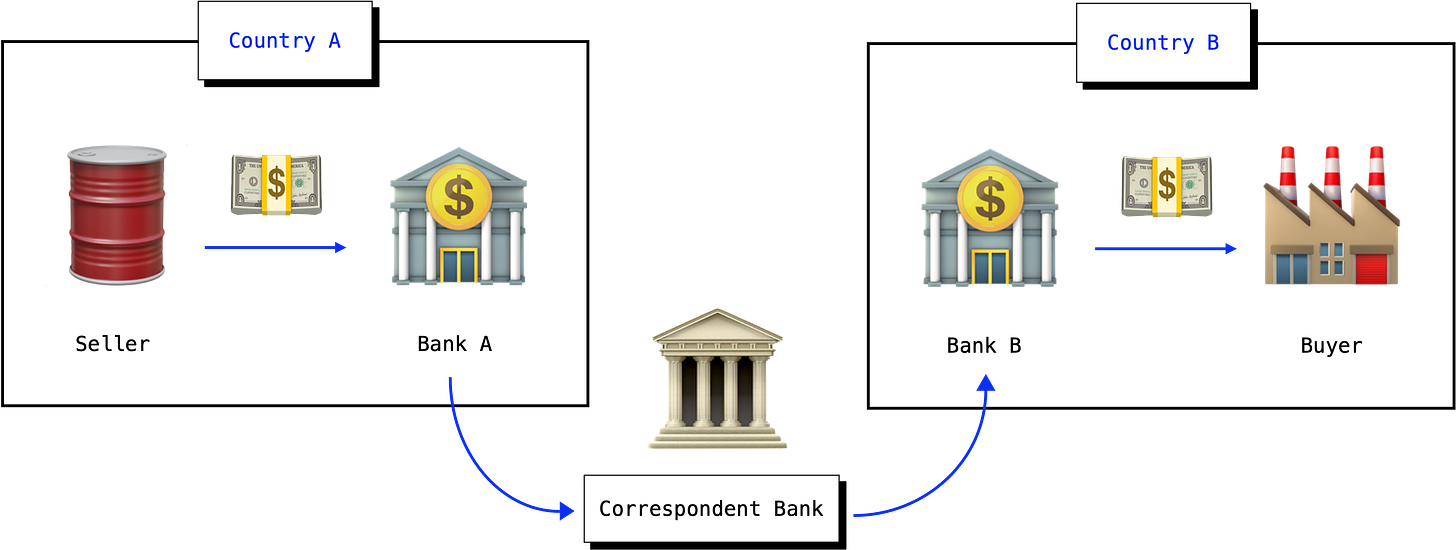

If an oil producer in the Middle East sold a barrel of oil to a buyer in Asia, the transaction (typically a wire-transfer) would likely take place in dollars. If the buyer and seller have an account with the same bank, the simple debit/credit is a “book transfer.” But it’s unlikely they share a bank. Maybe they transact regularly, in which case they maintain correspondent accounts1 with each other. In the absence of shared correspondent accounts, various correspondent banks exist that maintain account relationships with both banks. The counterparties transact via this intermediary. In the diagram below, the blue arrows indicate SWIFT instructions to debit or credit their accounts, with the correspondent bank acting as intermediary between the two counterparties. The majority of correspondent banking happens through banks domiciled in the US and EU.

Importantly, this is similar to how a central bank would conduct foreign exchange transactions. In Russia’s case, the immediate priority is stabilizing its currency, so the central bank will attempt to sell securities from its foreign exchange reserves to buy rubles. If the Bank of Russia offloads securities in the US, it will likely get dollars in return. It would then attempt to use the proceeds to acquire rubles. The seller of rubles is likely a Russian bank such as Sberbank, and the Bank of Russia would credit its correspondent account—likely at a shared correspondent bank—with foreign currency.

With 300 affiliated users sending 80% of its domestic financial communications, Russia is the second largest user of SWIFT, behind the U.S. A Russian bank could conduct these transactions without SWIFT, but this requires overcoming a number of linguistic and systems-based obstacles that make for a slow transmission. It’s not only cumbersome, it’s costly to process the transaction; higher transaction costs mean fewer potential counterparties. The takeaway is that the correspondent banking relationships are the most important factor—and the most punitive sanction.

Between the sanctions on major banks and SWIFT bans, the US is running a similar playbook for Russia as it did for Iran and the rational response from Russia and its investors is bank runs, capital flight, and panic hedging. But Russia built defenses for this.

The Bubble Russia Built

Under Putin, Russia fortified its economy as a result of two events: The 1998 Ruble Crisis and the sanctions levied in response to the invasion of Crimea in 2014. The crises Russia faced in the last half century will be the focus of an essay later this week, so we’ll treat these two briefly:

THE 1998 RUBLE CRISIS

In 1998, Russia recorded its first year of positive economic growth since the fall of the the Soviet Union. It heralded an overdue payoff for six years of economic reform, but was cut short by a financial crisis in Asia that dented demand for crude oil and spurred a speculative attack on the ruble. Russia was negotiating to reschedule foreign payments on Soviet debt, but investors were shaken by their ability to repay it. By mid-1998, Yeltsin had fired his government, Russian markets had collapsed, and the ruble was appreciating.

That these external events could have been avoided with prudent financial management stuck with Putin, then Secretary of Russia’s Security Council. When Putin was elected as Prime Minister in 2000, he steered Russia on a course of fiscal discipline and rising productivity which, combined with windfall earnings from energy, made Russia a darling of bondholders. Russia rode the recovery of oil prices and, importantly, didn’t spend commodity earnings on fiscal reforms. Instead, Putin began insuring Russia’s economy from shocks with measures such as the Stabilization Fund, which protected the country’s budget against oil price volatility while tamping inflation in ways the Russian central bank could not2.

THE 2014 CRIMEAN SANCTIONS

In 2014, Putin invaded Crimea and the West slapped Russia with sanctions. In response, Putin began constructing a financial fortress to entirely insulate Russia’s economy from the West.

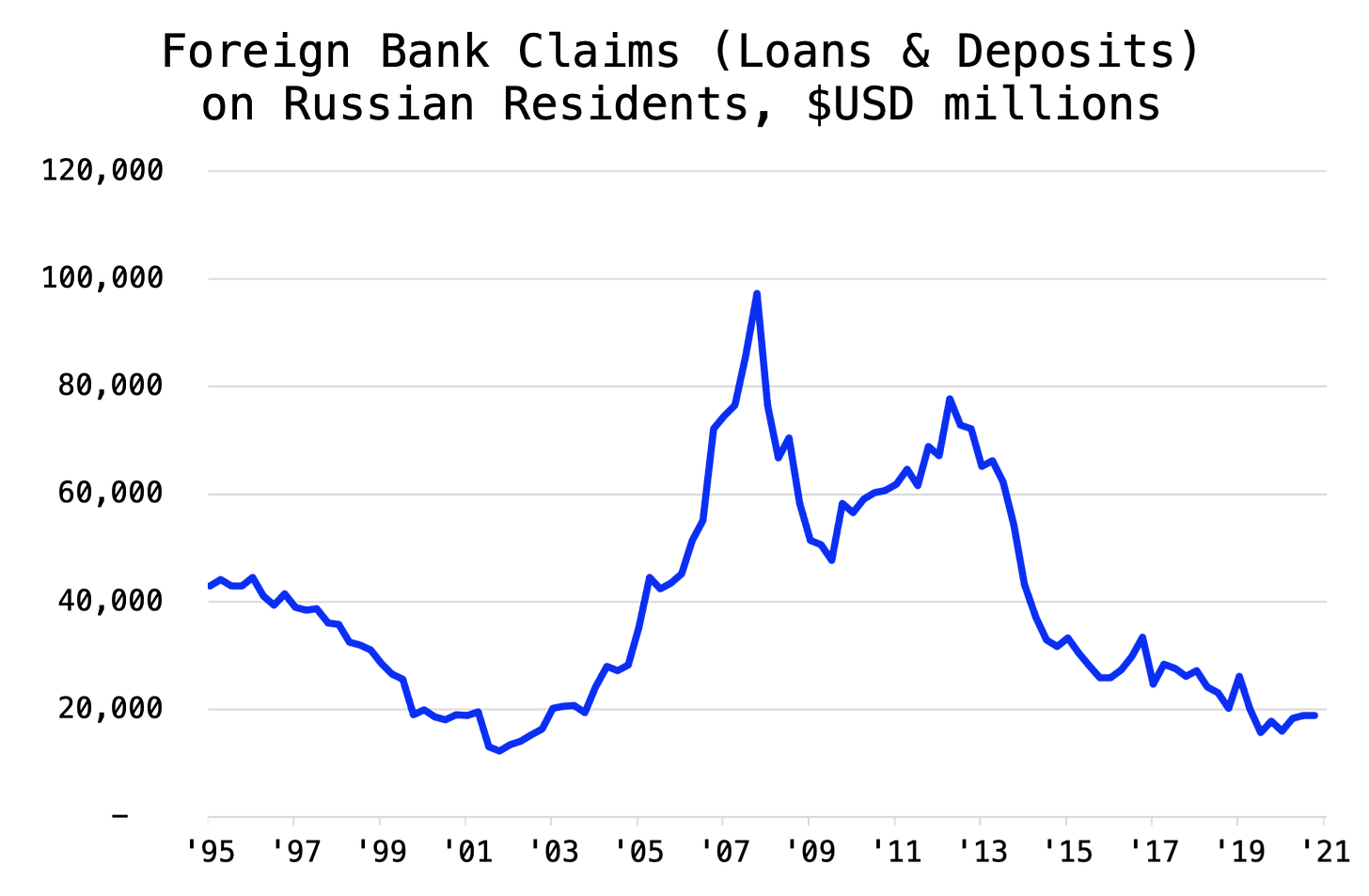

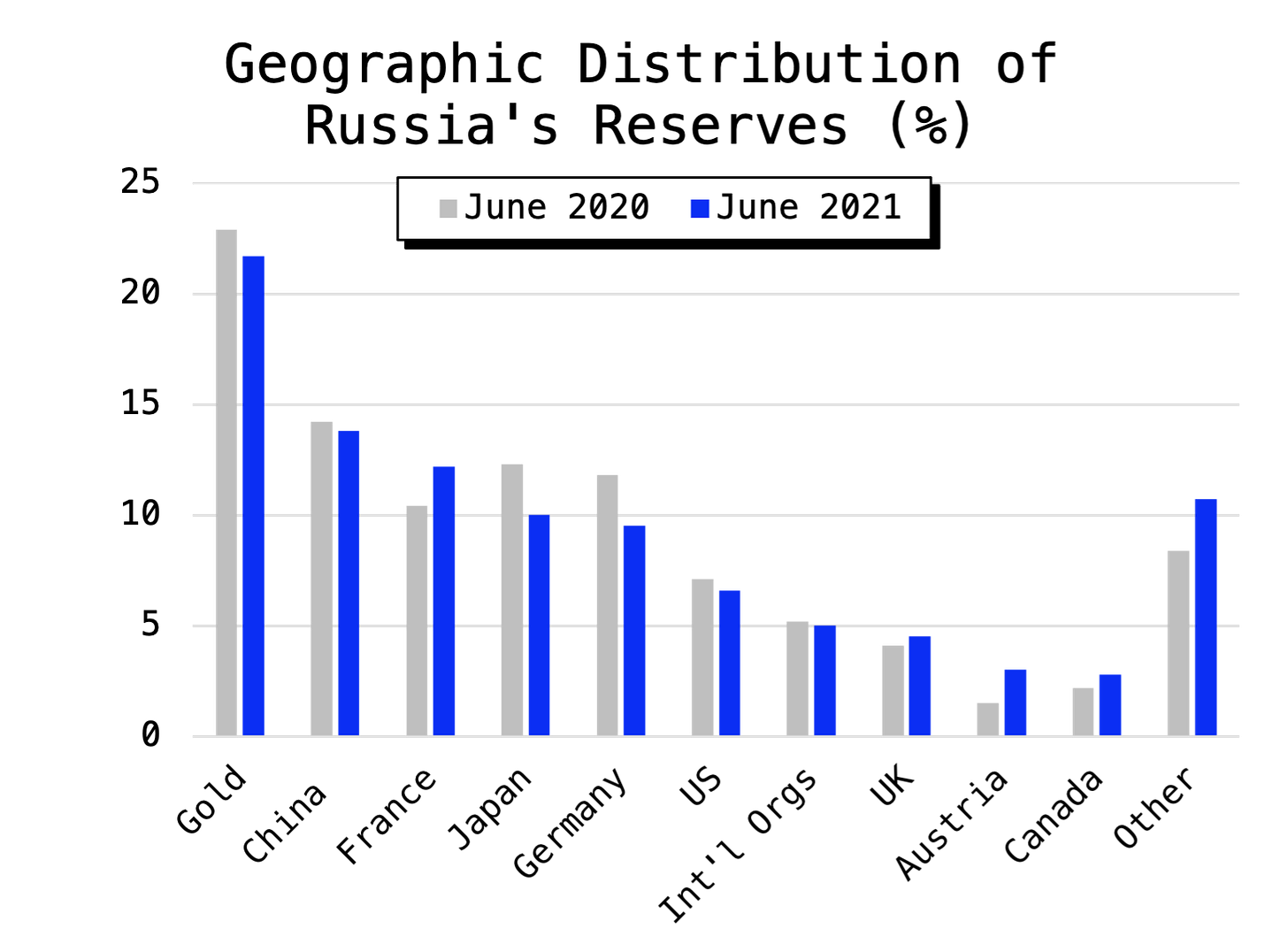

It developed a home-grown alternative to SWIFT, the System for Transfer of Financial Messages3 (SPFS). Today, SPFS counts 400 users from Russia and former Soviet states. For domestic payments, the Mir payment system, originally conceived of by Russia and the WorldBank in 2000, was finally launched in 2014 as an alternative to western payment systems (Visa, MasterCard). Today, less trade and fewer financial transactions in and out of Russia are conducted in dollars. Russia conducts $46 billion in foreign exchange transactions daily and about $37 billion of this is cleared in USD through foreign banks. But exports are mainly priced in euros. Wealthy Russians know better than to hold assets in foreign banks; what’s left is mostly Austria, France, and Italy.

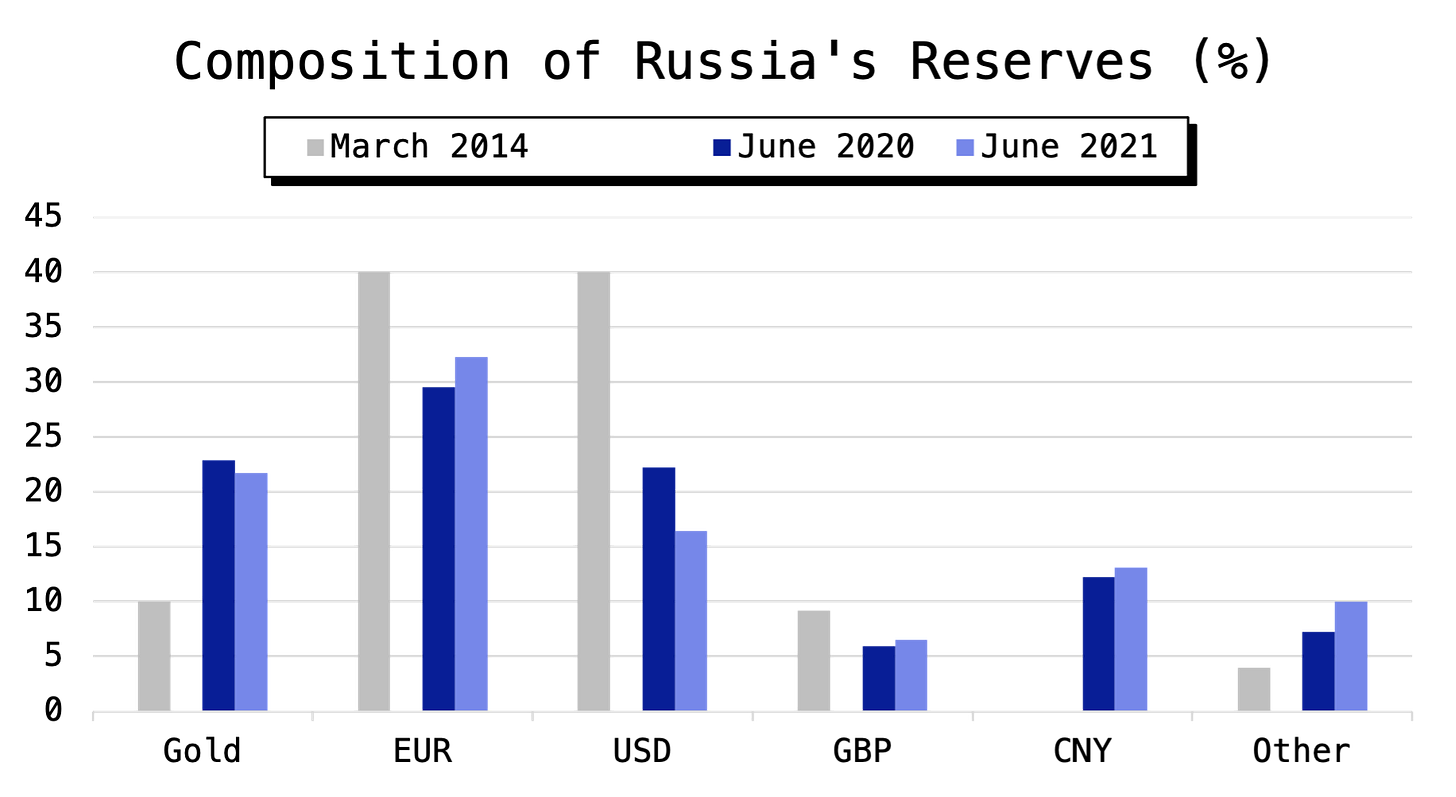

But before Russia worried what liabilities it had lying around in private banks throughout the world, it was intent on accumulating assets it could use to support the economy under stress. In Russia’s eyes, its greatest bulwark was its foreign reserves—what Adam Tooze has called “the foundation of Putin’s autonomy in international affairs.”

Russian Reserves

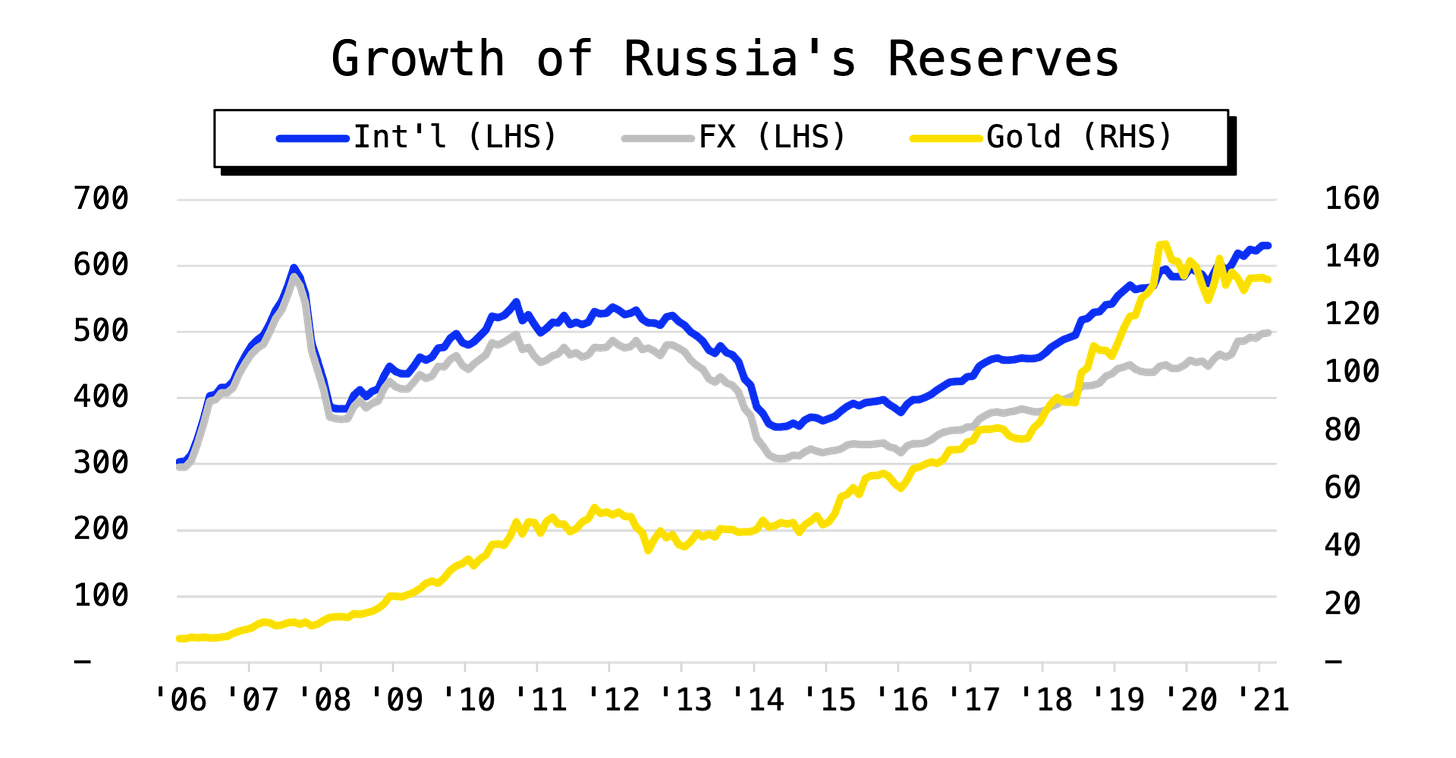

The standard minimum level of reserves is three months of imports—for Russia, this would sum to about $75 billion. Since 2014, Russia built its international reserves to over $630 billion (40% of GDP), of which 60%–75% is believed to be liquid foreign exchange reserves. This amount is less than the emerging market economy average of 80% of GDP, but far greater than the 9% of GDP among EU central banks. It far exceeds the amount necessary to service its external borrowing obligations or to manage a financial crisis such as 1998.

At first, much of these reserves were in dollars, euros, and, increasingly, gold. Incredibly, Russia now holds more gold bullion—2,300 tonnes of it, totaling $132 billion—than reserves at foreign central banks. All of it is kept onshore.

This saving and stockpiling was the fiscal discipline Putin admired and strove for. But what are these foreign exchange reserves good for?

Emerging markets hold higher reserves to reduce volatility, which lowers their borrowing costs. Shocks such as the Asian financial crisis hit emerging economies particularly hard. Piles of foreign currency can be used to pay for imports, which are denominated in foreign currencies. Exports remain competitive because the exchange rate is held down by a central bank that can sell its foreign currency to buy rubles, putting a floor under the price and stabilizing it in times of stress.

The day Moscow sent troops into Ukraine, the ruble fell to all-time lows. This is extremely dangerous: a rapidly depreciating currency makes it harder to pay off foreign debts and leads to higher prices on imported goods and lower returns on exports—upon which Russia is existentially dependent. Moreover, with a worthless currency, the Bank of Russia is unable to initiate automatic or policy stabilizers that might quell a crisis—the central bank can continue printing rubles that crater in value. Then there are the secondary effects, of capital flights, margin calls, and the likes.

So, the Bank of Russia started to sell foreign currency from its reserves on the forex market and buy rubles.

"Thank god we have enough forex liquidity and enough forex reserves” — Anton Siluanov, Finance Minister of Russia, 16 February 2022

Despite inflation, bank runs, and illiquid markets, it's thought that Russia would have room to run because of this war chest of reserves. If the reserves are so important to Russia, it’s important to understand their true value—and who actually controls them. This changed once the West levied sanctions on the steward of these reserves, the Bank of Russia.

Sanctioning the Central Bank

Although the central banks of Venezuela and Iran have been sanctioned, it is unprecedented for the central bank of a member of the G20.

Seeing the Bank of Russia’s reserves as a way to manage the crisis wrought by Western sanctions, the allies began chipping away at them.

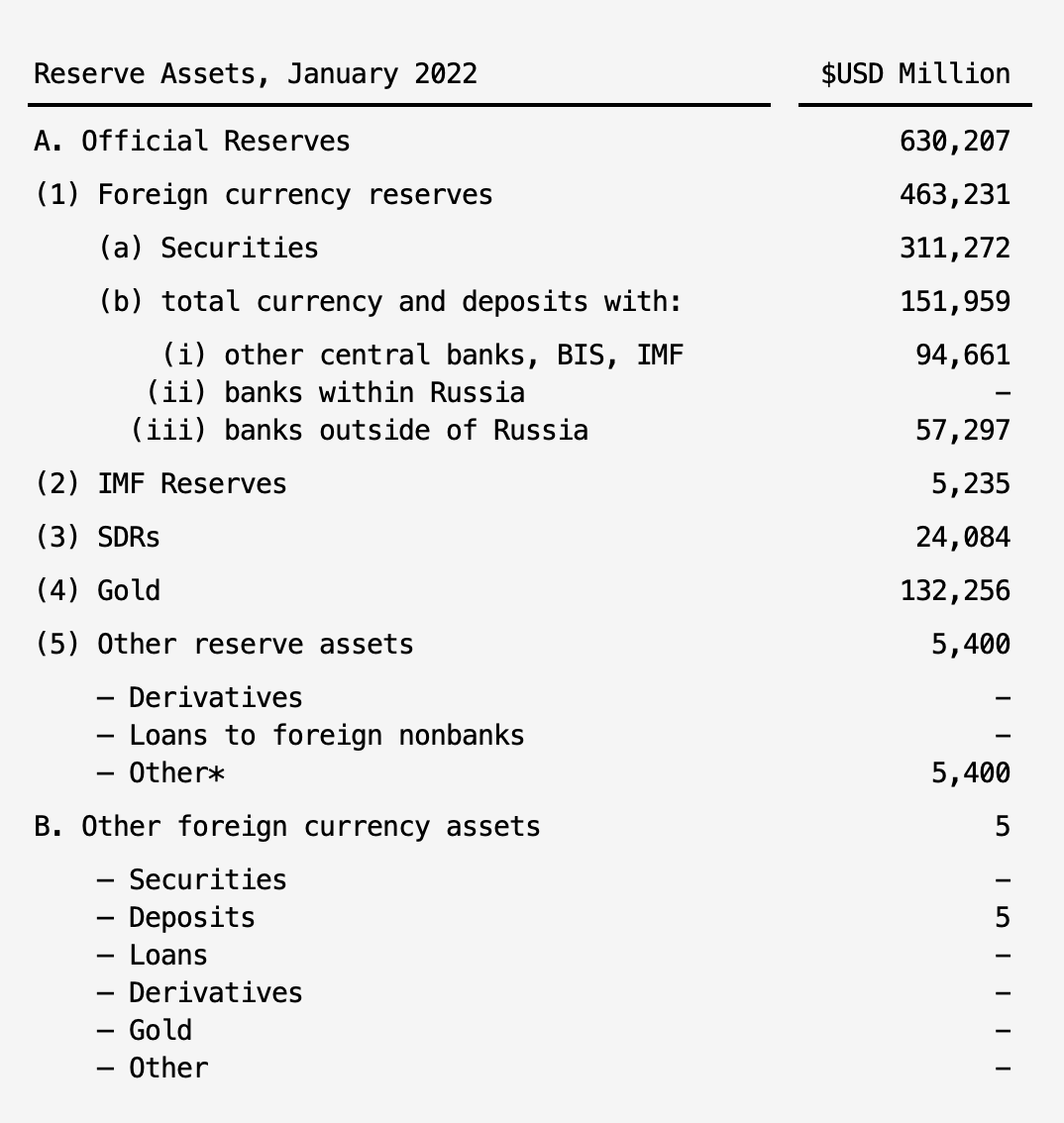

Following another barrage of sanctions over the weekend, a few deductions must be made from Putin’s $630 billion bulwark (well-summarized by Alphaville)

Securities ($311 billion) — All indications suggest the Bank of Russia’s holdings4 are marketable and liquid. So, the US has blocked the intermediaries who would be involved in a sale of securities: the brokers, custodians, foreign-exchange dealers, and correspondent banks.

Currency & Deposits ($152 billion) — Two-thirds of this is held in foreign central banks, the BIS, and the IMF. Nearly half of this is frozen: the US, UK, EU, and Canada have sanctioned the central bank, and the BIS will observe these sanctions.

Deposits at private banks ($57 billion) — Over half of this is likely deposited in banks in the US, EU, and UK. Although the others may be allowed to transact with the central bank, they may not want to.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that about $200 billion in local deposits are non-ruble. A ~10% increase in dollarization of deposits by Russians panicking about a falling ruble could drain another $100 billion of reserves.

Without access to international markets where Russia might sell its gold for currency, it could be reduced, as Iran was, to bartering. However, if Russia’s selling gold at a discount, buyers may emerge.

We don’t yet know where the remaining reserves are held exactly, only a vague country-level breakdown from the central bank.

About $300 billion of foreign currency is held offshore—likely $200 billion in FX swaps and $100 billion in deposits at foreign banks, according to Zoltan Pozsar. Wherever they are, Russia may own these reserves, but they may not control them. These assets were lent out; the owners—central banks or private banks—are now forbidden from returning them. Other than deposits in Chinese banks, these reserves are likely out of reach now.

Despite Putin’s efforts, Russia was not invulnerable. He stopped short of economic autarky—his only way to truly insulate Russia from the West. Of his many apparent miscalculations, the sanctioning of the Bank of Russia was an extremely important, if pardonable, one.

But perhaps the reserves weren’t so defensible after all. What domestic spending and fiscal reforms did Putin sacrifice to stockpile reserves? Was Putin foolish for promising succor with a large reserve balance?

As Nick Trickett noted in the Riddle, reserves are no more a sign of a stable economy than an expensive health insurance policy signals good health. A lack of public spending implies a greater measure of private borrowing. Investment and domestic demand and consumption suffer. Between 2013 and 2022, household borrowing increase 219%. While the state maintains its public debt at an attractive 16% of GDP, private debt was 215% of GDP in 2020. Borrower are particularly vulnerable in a situation the central bank has dryly called, “non-standard.”

The effects, of course, spread throughout the economy. How is Russia coping with this?

The Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Russia asked exporters to sell 80% of their foreign currency holdings. Controversially, the West hasn’t sanctioned Russia’s energy suppliers. The EU continues to pay Russian producers for oil and gas, which they turn into rubles. The central bank has contrived an exchange control that substitutes private balance sheets for the central bank’s own, which is frozen.

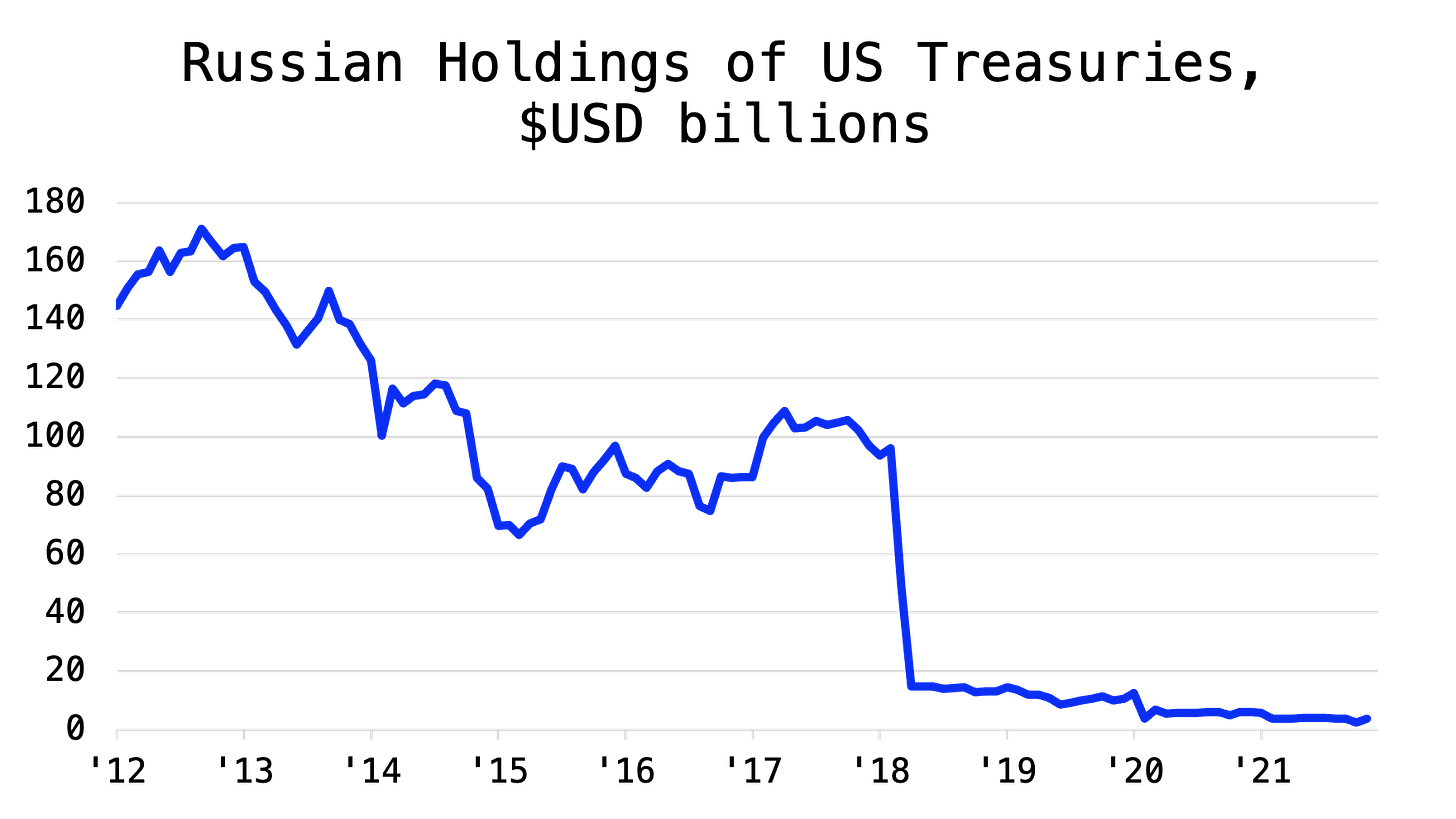

The central bank has two policy options: raising interest rates, which it did on Monday, and capital controls. On Tuesday, it banned coupon payments to foreign owners of ruble bonds. It doesn’t have dollar swap lines with the Fed, and Russia sold its stock of Treasuries in 2018 so it has none to repo with the new Fed’s new FIMA facility.

These Treasuries were likely moved to the Cayman Islands and Belgium, then invested in short-term money markets, lending its dollars in exchange for non-dollar collateral.

The question then becomes one of contagion: will the West’s wrath backfire?

Klaas Knot, who heads the Financial Stability Board, cautioned the West on collateral damage from sanctions well before the first tanks rolled over Ukraine’s border. The concern on everyone’s mind as the markets opened on Monday morning was, would enough dollar funding be available in the market?

Although immediate consequences may not be severe, the fragility these actions introduce to financial markets have consequences in the short-run for the unwinding of easy-money policies deployed by central banks in response to COVID-19. In the long-run, the severity of these sanctions will diminish the dollar’s role in financial markets. (There are reasons China would want to hasten this; I’ve written about those here.)

Sanctions: Signals & Follow-through

Sanctions are about signaling. US and EU sanctions on Russia’s central bank had a marked effect on Russia’s fragile economy even before these countries ironed out the details. Two questions arise: first, is the signal getting through to the Russian people? One ostensible goal of the sanctions is to ignite a populist uprising—or a revolt of the oligarchs—against Putin. But Putin has built a bubble around Russian media content, less sophisticated than China’s but nearly as effective. Early reports indicate the state-run media is spinning the sanctions as an aggressive release of pent-up antipathy toward everyday Russian civilians. Sanctions have signaled the West’s unity that message has clearly been received by Putin. So long as he remains in power, though, he controls how much of that signal reaches the 144 million people under his reign.

The second question is if it’s just signaling, or if there will be follow-through. In other words, the degree to which we’ll know just how effective each sanction is. This will take time.

Major sanctions by the West are levied through Treasury’s OFAC (Office of Foreign Assets Control) in the US, the EU sanctions list maintained by the European Commission, the Consolidated UN Security Council Sanctions List and the G7’s Financial Action Task Force (FATF) list of high-risk and non-cooperative jurisdictions.

Historically, European sanctions enforcement has been lax. US enforcement is more rigorous, but follows a “trust but verify” approach relying on self-reporting by financial institutions. Lapses in self-reporting are later discovered during audits and examinations of these financial institutions. For the consequences of these lapses, look no further than the record $8.9 billion fine of BNP for transacting with sanctioned entities from Iran, Sudan, and Cuba.

To be clear, there isn’t a reason to think financial institutions will evade sanctions on Russia anymore than they have in the past. After all, developed market exposures to Russia aren’t terribly high; only around $14 billion in Russian public debt is held by US institutions.

But it’s worth remembering that one consequence of real-time payments settlement means that the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, through which the dollar-denominated portion of foreign exchange transactions (~86% of total forex transactions) must flow, does not conduct OFAC checks. The parties to the transactions run the checks. Inevitably, not everyone will abide by them, intentionally or not.

Sanctions carry enormous signaling effect. Amid systemic bank runs and dollarization, we can expect a harsh credit crunch, continued capital outflows stymied by controls, and a drain on reserves and any available liquidity in order to prop up a currency that will inevitably fall further as debt will have to be monetized. In other words, a brutal collapse of Russia’s financial system seems imminent.